Uriel Araujo, researcher with a focus on international and ethnic conflicts

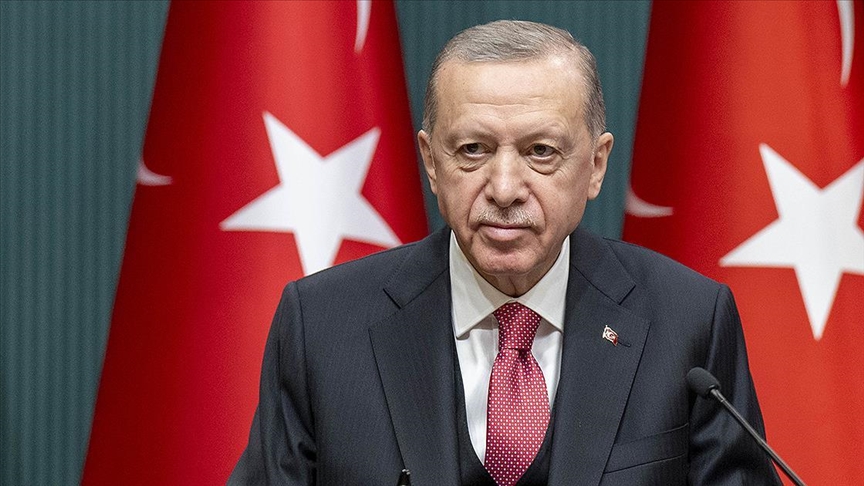

US-Turkish differences are on the rise and incumbent president Recep Tayyip Erdogan might be facing his most difficult election in 20 years. Erdogan’s domestic problems are well known: the country now experiances a 55 percent inflation and last October it had reached a 25-year high of 85.5%. Turkey’s currency has also lost 60 percent of its value against the dollar since early 2021.

In addition, the tragedy that ensued after the earthquake last month (around 50,000 people dead) has also sparked some outrage: many believe the disaster was made worse by poor urban planning and bad crisis management. Recent polls indicate that Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu, the opposition candidate, is leading by over 10 percentage points, just weeks before the upcoming election. Polls also suggest that the Nation Alliance, a six-party opposition bloc, could get the highest number of seats this time.

Even though Erdogan faces so many internal problems, he might still win the election. Since the 2016 failed military coup against him, the Turkish President has increased his powers. Some analysts, such as Sinan Ciddi, professor of national security studies at the US Marine Corps University and author of the book “Kemalism in Turkish Politics”, believe that he can make good use of Turkish media (which supposedly is largely controlled by his AK Party) to overcome some of his problems. This scenario may provide the political West with sufficient basis to push a narrative about a “dictatorship” in Turkey, thus casting doubts on the legitimacy of any Erdogan’s election victory.

Foreign Correspondent Jamie Dettmer argues that one should expect Erdogan to contest any election defeat. Ciddi in turn believes “judges and elections officials loyal to Erdogan may overturn the results” and thus “he may not relinquish power after having lost the election.”

The fact that the West routinely weaponizes the issue of human rights and democracy, often hypocritically, is well known. The human rights issue certainly plays an important propaganda part in the wars of narratives that are part of many frictions Western powers are involved in today. Such a narrative may be losing force today, but much of Western rhetoric and diplomacy campaigns is still based on it.

The Madrid Summit Declaration, issued at the 2022 NATO Summit, stated that there has been an “unprecedented level of cooperation with the European Union”, and vows to strengthen the “strategic partnership” with the bloc. During that summit, China was, for the first time, addressed as a “challenge” to the Alliance’s “interests, security”, and also its “values”. The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) describes itself, in its official website, as an organization promoting “democratic values”.

Institutionally, that has always been so, at least in theory, but today democratic values (framed in a Western understanding of the concept) are increasingly in the spotlight, in spite of the aforementioned hypocrisy. Such hypocrisy could allow for accommodating members that do not necessarily abide to Western notions of democratic rule. However, such an accommodation may become increasingly harder to be pursued, especially when Erdogan’s Turkey is seen as a kind of a hindrance to the Alliance’s strategic goals pertaining to Nordic expansion.

The aforementioned US Marine Corps University scholar Sinan Ciddi also argues that no American-Turkish rapprochement is possible under Erdogan. Contesting Turkey’s Ambassador Murat Mercan recent remarks about the inevitability of “gradual rapprochement between Turkey and the United States”, Ciddi portrays the Turkish leader as an “opponent of democratic governance”, who “shares none of the values that define and undergird the transatlantic alliance that Turkey was an integral and trusted member of.” He concludes by saying that “the United States should not settle for a bad ally.”

As I have written, Ankara has employed Pan-Turkist, Neo-Ottomanism و Turanist ideas as a tool for soft power. Its greater ambitions also threaten peace in Central Asia and even beyond. Although Turkey has been a NATO member since 1952, experts have been talking about a Turkish “Eastern turn” since at least 2016, when it started pursuing a much more aggressive and independent foreign policy seeking integration with Arab and Muslim nations. This can certainly further complicate Turkey’s already complex relationship with Russia. In spite of these tensions, Ankara and Moscow have managed so far to maintain stable bilateral relations. With the West, however, the relationship has only been declining.

Already in 2019, Washington was proposing new sanctions against the Republic of Turkey over the issue of Turkish acquisition of the Russian S-400 missile defense system. In August 2022 Ankara was planning to receive the second S-400 batch anyway – a still ongoing issue.

Turkey-US divergences on NATO’s Nordic expansion and on the Kurdish matter (two issues that I have argued to be related), might be the last straw. The Turkish opposition in fact has promised to end Ankara’s veto on NATO membership for Finland and Sweden and to “unfreeze” EU accession talks.

If Erdogan remains “inflexible” on the issue of Sweden, then what can we expect from the US? At this point, one can only speculate, but based on what we know about Washington’s modus operandi, it would not be too far-fetched to expect it to start a diplomatic campaign against Ankara in the likely event of an Erdogan reelection. Dependending on how that develops, one could also expect the US to clandestinely support opposition and even Kurdish groups in attempts to destabilize Erdogan’s presidency or even aiming at regime change.