By Dr. Vladislav B. Sotirovic, Research Fellow at Centre for Geostrategic Studies

The Doctrine (1823)

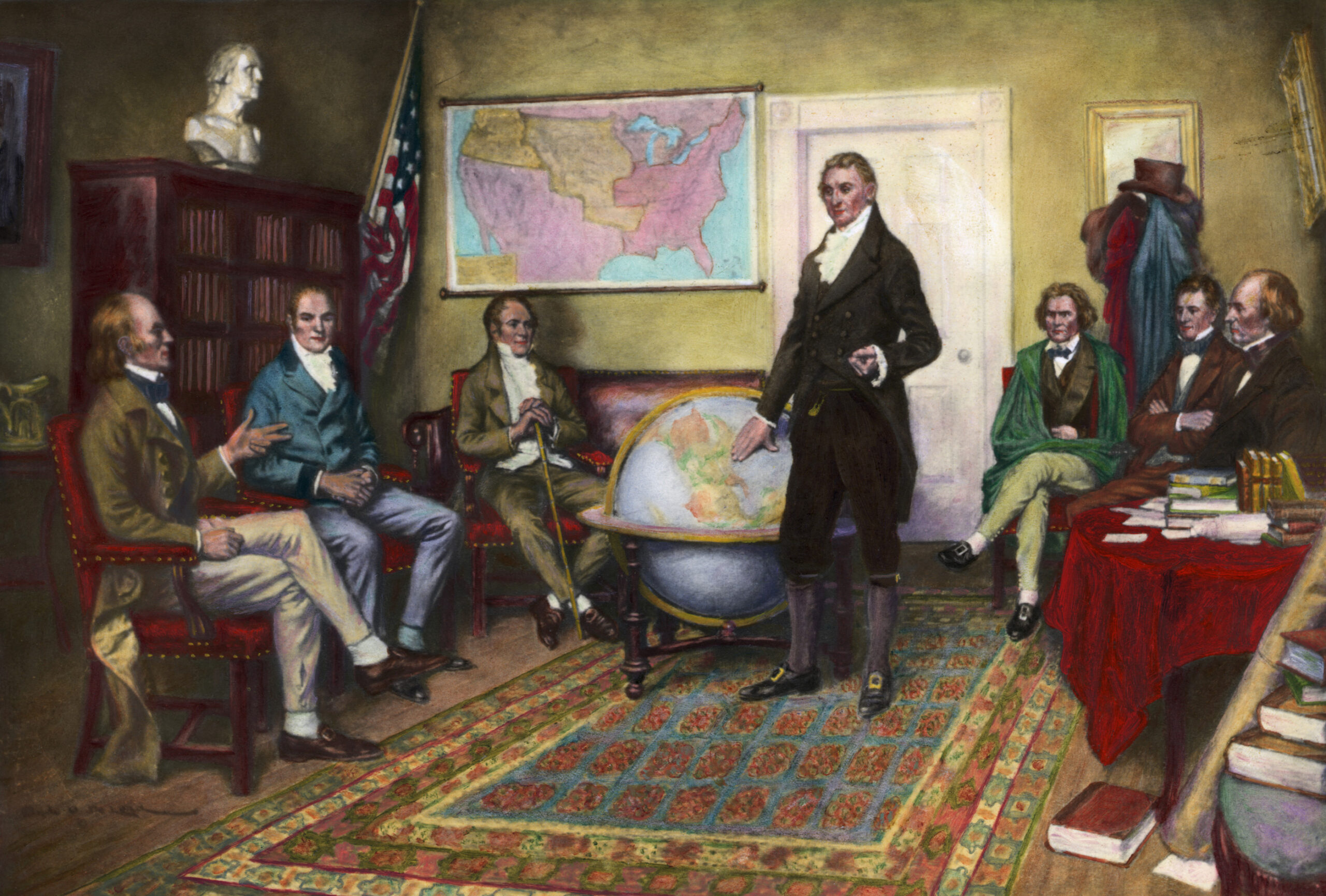

The doctrine was presented by the 5-th U.S. President James Monroe (1817−1825) in 1823 as an official warning to (West) European powers that any European policy of imperialistic expansionism on the ground of the Americas (North, Central, and South or Anglo-Francophone and Latin, i.e., Spanish & Portuguese) was going to be taken into account by Washington as a threat to the U.S. national interests. In fact, the doctrine proclaimed the Americas as the sole business of the U.S. without any involvement or/and interruption from the outside world. In other words, James Monroe proclaimed the exclusive U.S. economic, financial, and geopolitical rights to deal (exploit) with the Americas (including Canada as well). The doctrine was later extended with practical consequences by both 26-th U.S. President Theodore Roosevelt (1901−1909) and 28-th U. S. President Thomas Woodrow Wilson (1913−1921) who used it to formally justify American imperialistic policies in several countries from Latin America from Mexico to Colombia.

James Monroe (1758−1831) was the U.S. Democratic Republican statesman and the U.S. President. He is remembered for two reasons: 1) In 1803 being a minister to France under U.S. President Jefferson he negotiated and finally ratified the so-called “Louisiana Purchase”, by which a large territory formally owned by (Napoléonic) France was sold to the USA (as Napoléon needed extra financial sources for his wars in Europe); 2) However, James Monroe is mainly remembered as the creator of the Monroe Doctrine which, in fact, drafted the U.S. imperialistic policy in the future.

What is the Monroe Doctrine? It is the U.S. foreign policy formal (diplomatic) declaration that was warning (West) European powers (in fact, the UK, Spain, Portugal, and France) against further colonization of the Americas (the New World) but, as well as, against intervention in the governments within the American hemisphere. As a counteroffer, the doctrine disclaimed any intention of Washington to take part in European political affairs (that was, however, valid till April 1917 when the U.S. took direct participation in WWI on European soil followed by the American military intervention in Russia during the Russian Civil War of 1917−1921).

The background of the doctrine that was uttered by President James Monroe in his annual speech to the U.S. Congress in 1823, was, at first glance, the political threat of military intervention by the post-Napoleonic Holy Alliance to restore the colonies of Spain in Latin America which already declared their independence from Madrid. However, it became soon clear that the U.S. imperialistic policy had to fill the vacuum in Latin America after the withdrawal of the Spanish power and administration.

The Monroe Doctrine was from time to time applied by the U.S. foreign policy in the Americas. Nevertheless, after the development of territorial interests in Central America and the Caribbean, it became a tenet of U.S. foreign policy. The doctrine in the first part of the 20й century was developed into a policy in which Washington concerned the U.S. as responsible for the security of the Americas – an umbrella of U.S. geopolitical colonization of the Americas especially during the Cold War. As a result, such policy consistently complicated U.S. relations with Latin American countries, and only local dictatorships sponsored by Washington could control the people’s anti-American sentiments.

It is understood by political scientists that, in fact, it was in the cause of the balance that London influenced Washington to issue the Monroe Doctrine – the doctrine announced by President James Monroe to Congress on December 2nd, 1823. We have to keep in mind that the doctrine originally stated that (West) European states could not re-colonize the Americas or interfere in the affairs of already independent states of North and South America. At the moment, such an attitude was reflecting the U.S. and the U.K.’s concern about West European interference within the Western hemisphere, especially any effort by Spain to regain control over former colonial possessions in Latin America. Nonetheless, the focal slogan of the Monroe Doctrine – “America to Americans” in the following years, basically, inspired U.S. colonial imperialism and since 1867 and especially 1898 became transformed into the policy of “The Americas to the U.S.A.”.

President Monroe promulgated his doctrine for the reason that he saw an opportunity for the special geopolitical role of Washington in the Americas from Alaska to Patagonia. However, originally, beating the Spanish and French colonial influences in the Americas was not imaginable at the time of the declaration without the British Royal Navy. Truly speaking, the aim of the U.K. was not to assist the U.S. but to beat France – a country that at that time dominated Spain. Therefore, the British Foreign Secretary George Canning (1770−1827), actually, encouraged the policy of Washington as a good way to count down Spanish (in fact, French) colonial power. Shortly, the U.S. administration issued the Monroe Doctrine formally to prevent any further effort by Spain (and France) to regain its lost possessions in the New World (the Americas). Nevertheless, in practice, according to the doctrine, all European states have been obliged to respect the Western hemisphere as an exclusive sphere of geopolitical, financial, and economic influence by the U.S.A.

The first consequences (1897−1916)

The 1897−1903 Alaska border dispute with neighboring Canada (Dominion since 1867) was the first direct implementation of the Monroe Doctrine concerning the U.S. foreign policy with, in fact, the final geopolitical intention to incorporate Canada into the U.S.A. In other words, the rush to the Klondike gold fields in 1897 (land between Alaska and Canada) brought the dispute near the war between the two states. Canada feared the loss of the territories in the northwest. However, a politically oriented tribunal established to solve the problem with the U.K. judge holding the casting vote simply favored in 1903 the boundary line between Canada and the U.S. proposed by Washington.

The U.S. military intervention in the insurrection in Cuba in 1898 directly provoked the war with Spain. As the war became extremely successful for Washington, the U.S. obtained a protectorate over Cuba in 1903. However, the constant local revolts against U.S. rule brought several American military interventions on the island from 1906 to 1922. Nevertheless, similar U.S. military interventions happened in the Caribbean Dominican Republic twice – in 1905 and 1916−1924 followed in Haiti (1915−1934), and in Nicaragua (1909−1933). The next stage of the U.S. colonial imperialistic policy in Latin America according to the Monroe Doctrine was in 1917 when under Washington’s military pressure Denmark was forced to formally sell the Virgin Islands to the U.S. Nonetheless, the U.S. aggressive policy on Mexico in meanwhile brought two abortive American military interventions in that country in 1914 (invasion on Tampico and Veracruz) and 1916 (invasion across Rio Grande on Mexican provinces of Chihuahua, Coahuila, and Nuevo León).

Probably, the focal geopolitical and economic success of the U.S.A. in Latin America following the Monroe Doctrine was to obtain the Panama Canal zone’s control and protection (in fact, exploitation). Under the treaty with Panama (a former territory of Colombia taken out by the U.S.) in 1903 the U.S. leases the Panama Canal zone in perpetuity. However, at the same time, according to the treaty, Washington had to possess the zone as “if it were sovereign”. In fact, such contradictory diplomatic language caused unsolvable arguments from both sides. To keep in mind, the Panama Canal zone is 10 miles wide being bisected by the Canal which, contrary to the Suez Canal, has locks.

Woodrow Wilson and the Monroe Doctrine

The 28й U.S. President Woodrow Wilson (1913−1921) proclaimed to the U.S. Senate in January 1917 that both the principles and policies of the U.S.A. had to be accepted by the rest of the world as they were those of all mankind. More precisely, he argued that all nations of the world should “with one accord adopt the doctrine of President Monroe as the doctrine of the world” continuing that “no nation should seek to extend its polity over any other nation or people”. A result of proclaiming the 1923 Monroe Doctrine as the doctrine of all nations, should be “that every people should be left free to determine its own polity, its own way of development, unhindered, unthreatened, unafraid, the little along with the great and powerful”. That was, in fact, a formal expression of universalizing international relations founded on President Monroe’s doctrine (which originally dealt only with the Americas but now it was implemented to the whole world).

However, in practice, a different perspective of the implementation of the Monroe Doctrine by Washington (and others) prevailed as even within the Western Hemisphere the impact of the Monroe Doctrine was other than benign. The doctrine, unfortunately, even during the presidency of W. Wilson did not serve as a guarantee that all nations would be permitted to determine their destiny “unhindered, unthreatened, and unafraid” but, in fact, as a mechanism for making order of the relations between the stronger and weaker states either in regional or global politics according to imposed terms dictated by the stronger.

Actually, from the time of W. Wilson’s presidency, the 1823 Monroe Doctrine had evolved into a rationale for both U.S. military intervention and the expansion of U.S. power (hard and soft). W. Wilson, in 1915, was eager to see democracy prevail in the Caribbean being at the same time unwilling to tolerate anything that smacked of radicalism or instability and, therefore, he sent U.S. military troops into Haiti. Next year (1916), just several weeks before W. Wilson gave his January 1917 speech, American troops occupied the Dominican Republic. Nevertheless, the U.S. stay in each instance proved to be an extended one, and in neither country occupied by American troops did democracy flower as a result.

Woodrow Wilson was very confident that he and his administration had the right to make a destiny of the Mexican Revolution and were eager at the same time to teach others to “elect good men”. Consequently, his administration persistently interfered in Mexican internal affairs and even organized military expeditions into Mexico twice: in 1914 and 1916. Nonetheless, W. Wilson’s quest to make the revolution more democratic was abortive and he, basically, succeeded only in poisoning the relations with neighboring Mexico for a longer time. However, according to W. Wilson, all these U.S. military actions had the best intentions and were done following the 1823 Monroe Doctrine.

Last words

In conclusion, the ideological foundation for such American colonial imperialism in the Americas since the end of the 19й century was the 1823 Monroe Doctrine which implied an intention to treat the Americas (especially Latin America) as the exclusive geopolitical, economic, and financial sphere of influence by the U.S.A.

Many official advocates of an “open world” or “world without the border” (in fact, the globalists) are in essence proponents of M. Monroe’s doctrine and W. Wilson’s principles of a free world to implement U.S. principles and policies on a global scene. They, like W. Wilson himself, strictly reject the notion that others might construe American foreign policy as imperialistic. What is the climax of the matter, they advocate that the U.S. deserves to be above all other great powers (in fact, super- or even hyperpower) in order to employ their values to the rest of the world even using a power (soft or hard) to act on behalf of the global benefit. They propagate that openness is the cause of democracy, economic development, protection of human rights, and peace. However, in many cases, this openness is just a formal framework for the American crucial influence around the world which gradually was implemented after the official presentation of the Monroe Doctrine in 1823.

Personal disclaimer: The author writes for this publication in a private capacity which is unrepresentative of anyone or any organization except for his own personal views. Nothing written by the author should ever be conflated with the editorial views or official positions of any other media outlet or institution.